Bach for Two Plectrum Classical Guitars

I listened to an advance copy of Matthew Hough’s soon-to-be-released CD a few days ago (thanks, Meg!) and liked it. It’s a couple of guys playing Bach on classical guitars, but using flat-picks. It’s a good sound, sort of folksy and friendly, easy-going.

Matthew Hough: Music from the Notebook of Anna Magdalena Bach. He also has the sheet music available.

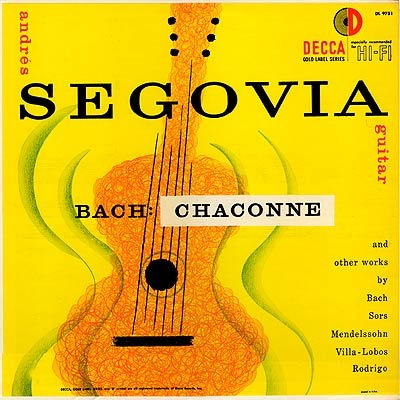

The Chaconne

In 1935, Segovia premiered his milestone transcription of Bach’s Chaconne and vaulted the classical guitar into the realm of “serious” instruments. In 1955, he recorded it. Thanks to Segovia, we classical guitarists feel like we own a little piece of this monumental masterpiece for solo violin.

Still, it behooves us to study great violinists playing this piece — and until late last night I thought I could do no better than to study the legendary Jascha Heifetz playing the Chaconne. 20 years ago I found a VHS tape of Heifetz playing it. That tape was my greatest treasure for several years.

Segovia had a story he would tell whenever he talked about the Chaconne. According to Segovia, the famous violinist Enesco gave the following advice to a student: “You must study the Chaconne all your life, but you must not play it in public until you are 50, because it is very, very deep.”

I learned the Chaconne when I was 17, but I took that story to heart and refrained from playing it in public. I found the Heifetz video when I was 40. I watched it countless times, studying every nuance that I could grasp, including, toward the end of the piece, the subtle expressions of emotion that would pass across Heifetz’s famous “great stone face.” To see this giant in his 70th year deliver this music… well, it seemed to me that nothing could be better.

As I said, I’ve always thought Heifetz was the last word on the Chaconne. But then, in the wee hours last night, I was reading about this being the 50th year since the JFK assassination. I read that a week after the assassination, at the first road show of the musical Camelot, the audience broke down in uncontrollable grief when the title song was sung.

Reading further, I found many stories of musical tributes to JFK in 1963. Among them was this story about Isaac Stern:

[Stern] recalled when he was in Dallas the day that his friend, President John F. Kennedy, was assassinated. Sitting in a cafe at the Dallas airport, while waiting for a connecting flight to San Antonio, a devastated Stern and a friend downed a bottle of bourbon. Looking out the window, they could see Air Force One which was carrying Kennedy’s body.

The next night, Stern was scheduled to play the Sibelius Violin Concerto in D Minor with the San Antonio Symphony, but at the morning rehearsal he told the conductor that the piece seemed inappropriate.

The only thing he felt he could play was Bach. That night he told the 4,000 people in attendance that musicians sometimes pray by playing certain kinds of music, and that he prayed by playing the “soul-cleansing” music of Bach. Stern asked the audience not to applaud at the end.

While playing the Bach Chaconne, he wept uncontrollably. After he finished the piece, there was dead silence. He put his violin back in its case, left the auditorium and flew back to New York.

Baroque Ukulele – Samantha Muir

Nothing’s perfect? I used to think so.

Samantha says:

I recently read that the Ukulele is the happiest instrument in the world so I wanted to share some happiness! For those of you who are used to me playing the guitar, don’t worry, it’s not a case of “Josie, I shrank the Smallman,” it’s just me enjoying the summer holidays with my new pet….the uke, or jumping flea. Just to prove that even little things should be taken seriously I decided to play some Bach. This is a very nice arrangement of the 2nd Bourrée from Bach’s 4th Cello Suite by Tony Mizen and can be found in his book, The Baroque Ukulele.

The Torban

The torban is a sort of Ukrainian theorbo, according to Wikipedia:

The torban (also teorban or Ukrainian theorbo) is a Ukrainian musical instrument that combines the features of the Baroque Lute with those of the psaltery. The Тorban differs from the more common European Bass lute known as the Theorbo in that it had additional short treble strings (known as prystrunky) strung along the treble side of the soundboard. It appeared ca. 1700, probably influenced by the central European Theorbo and the Angelique which Cossack mercenaries would have encountered in the Thirty Years’ War, although the likelier possibility is that certain Tuliglowski, a paulite monk, was its inventor. The Torban was manufactured and used mainly in Ukraine, but also occasionally encountered in neighbouring Poland and Russia (only 3 luthiers could be identified from the surviving instruments). There are about 40 torbans in museums around the world, with the largest group of 14 instruments in St. Petersburg. The term “torban” was often misapplied in the vernacular in western Ukraine to any instrument of the Baroque Lute type until the early 20th century.

The surviving printed musical literature for torban is extremely limited, notwithstanding the widespread use of the instrument in Eastern Europe. It was an integral part of the urban oral culture in Ukraine, both in Russian and Polish (later Austro-Hungarian Empire) controlled parts of the country (after the split). To date the only notated examples of torban music recorded are a group of songs from the repertoire of Franz Widort collected by Ukrainian composer and ethnographer Mykola Lysenko and published in the “Kievskaya Starina” journal in 1892, and a collection of songs by Tomasz Padura published in Warsaw in 1844.

The multi-strung, expensive in manufacture, stringing, maintenance and technically difficult fretted torban was considered an instrument of Ukrainian gentry, although most of its practitioners were Ukrainians and Jews of low birth, with a few aristocratic exceptions (e.g. Ivan Mazepa, Andrei Razumovsky, Padura, Rzewucki), a few virtuoso players are known by their reputation, such as Andrey Sychra (from Lithuania), and the Widort family, originally from Austria, but active in Ukraine since late 18th century. The latter has produced 3 generations of torban players: Gregor Widort, his son Cajetan, and grandson Franz.

Such aristocratic associations sealed the instrument’s fate in the aftermath of the Russian Revolution: it was deemed insufficiently proletarian and was discouraged.

Bach: Rondo from Partita No.2 in C minor, BWV 826

It’s always a treat to see another Roman Gurochkin classical guitar video.

Bach: Prelude BWV 998 – Luciano Contini, Lute

Notice, along with all the other good qualities of this performance, how fittingly the tempo varies.